Introduction

This is the first of three posts that address:

1. Predicting the probability of a “positive” (reject H0H0) study before running the study

2. Interim analyses during the study

3. Evaluating study data in a meaningful way after the study is completed.

Topic 2. and 3. will be posted later.

The general linear model

Consider the general linear model with a single factor (One-way ANOVA) for a mean centered variable YijYij, Yij=Zij−¯ZYij=Zij−¯¯¯¯Z:

Yij=τj+ϵij where ∑τ=0. ϵij∼N(0,σ) and ∑τ=0. Can be expressed as Yi∼N(τi,σ).Consider the situation with two levels, j=1, 2, where the aim is to estimate θ=τ2−τ1. One Baysian model of Y is

Yi∼N(τi,σY) τi∼N(γi,στ) σ−2∼Inv−χ2(ν0,σ20)

For a completely randomized design the estimator ¯x1−¯x2 of θ has the property

¯x1−¯x2∼N(θ,√2σ2n)

where n is the number of observations for each factor level 1 and 2.

Study design

Frequentist sample size calculation

In order to make an an assertion that θ>0(H1), if α =2.5%, σ=2 and we require 80% power to declare statistical significance (make an “assertion of efficacy”, to quote Frank Harrell, watch it here) if the true value of θ = 1, then 63 evaluable subjects/group are needed. The (frequentist) probability conditional on θ = 1 of rejecting H0, P(reject H0|θ=1) is then 0.80. To achieve P(reject H0|θ=1)=0.90, 84 subjects/group are needed.

Probability of success of future study

Semi-bayesian probability of success (“assertion of efficacy”/Assurance)

Lets say (Gelman, et al)

θ|σ2∼N(θ0,τ20)

σ2∼Inv−χ2(ν0,σ20)

The hyperparameters θ0, τ0, ν0, σ0 are determined by information from a previous study. Let say the previous study had n=50/group, ¯x1−¯x2 = 0.5 and ˆσ = 2 for both groups. Then we can calculate the unconditional probability of rejecting H0.

P(reject H0)=∫θ,σP(reject H0|θ,σ2)⋅P(θ,σ2)dθσ

This is the approach referred to as Assurance proposed by Spiegelhalter & Freedman and developed by O´Hagan. The R package here was used for calculations:

library(assurance)

initial.data <- new.gaussian(delta.mu=0.5, sd1=2, sd2=2, m1=50, m2=50)

later.study <- new.twoArm(size=study.size(grp1.size=63, grp2.size=63),significance=0.05)

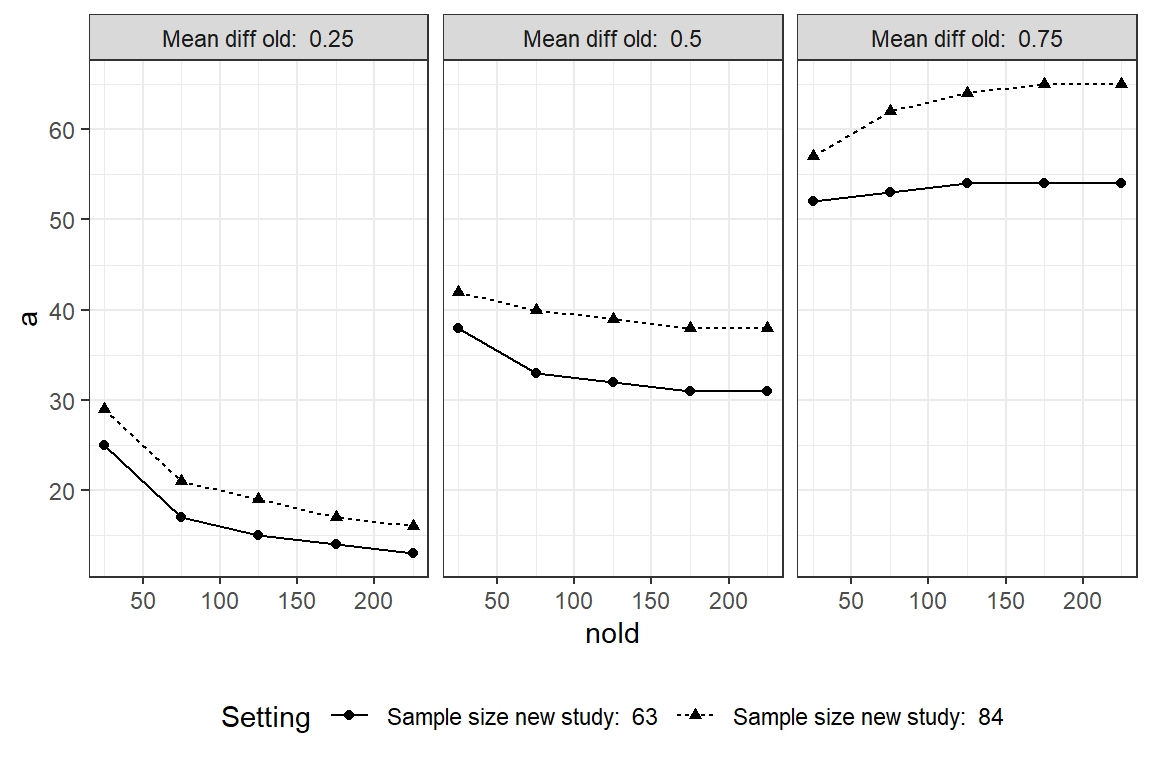

Assurance <- round(100*assurance(initial.data, later.study, 100000))Given the results from the previous study, P(reject H0)=35%. Given everything else equal, if the previous study had an observed effect of 1 instead of 0.5, then P(reject H0)=70%. How does the probability of success depend on the sample sizes from the previous and forthcoming study? How does the previously estimated effect influence? Given ˆσ = 2, we see that the larger the sample size of the previous study, the less will the assurance be in the in-between uncertain region around 50%. If the previously estimated effect is small (left panel) the assurance will decrease with study size.

Assurance will increase if the previous estimate indicate a larger effect. For a future study with 63 subjects/group a previous estimated effect of 1 based on a enormous study (>1000 subjects) the assurance will be 80% (the power). With 84 subjects assurance will be 90%. With a previous estimate of 0 assurance will tend to 2.5%.

Hmisc function gbayes2

gbayes2 also refer to Spiegelhalter and Freedman (1986) to compute the probability of correctly concluding that a new treatment is superior to a control. In the Hmisc manual it says “Even though gbayes2 assumes that the test statistic has a normal distribution with known variance (which is strongly a function of the sample size in the two treatment groups), the prior distribution function can be completely general.”. I interpret that the scale parameter σ of the likelihood has a prior with a spike at the value of anticipated standard error of the planned study, i.e. a constant. But this is in practice no limitation because the scale is a nuisance parameter and prior information of θ is only what interests us. I think the reason why we can still get closed form solutions without a conjugate prior distribution (we don´t estimate a posterior distribution here, though) is because is fixed σ (for the same reason Assurance relies on simulations) Assurance, is in principle gbayes2 but where the source of the prior belief (the previous study) is explicitly included, but this is of course not needed.

Again, given the previous study with n=50/group, ¯x1−¯x2 = 0.5 and ˆσ = 2. If we let

τ|n,σ=√2σ2n=√2⋅2250=0.40

library(Hmisc)

N<- 63

SD <- 2

SE <- sqrt(2/N)*SD;

prior0 <- function(delta)dnorm(delta, 0.5, sqrt(2/50)*2)

gb0<-round(100*gbayes2(sd = SE, prior = prior0, delta.w=0, alpha=0.05, upper=Inf))

prior1 <- function(delta)dnorm(delta, 1, sqrt(2/50)*2)

gb1<-round(100*gbayes2(sd = SE, prior = prior1, delta.w=0, alpha=0.05, upper=Inf))

prior1 <- function(delta)dnorm(delta, 1, 0.005)

gb2<-round(100*gbayes2(sd = SE, prior = prior1, delta.w=0, alpha=0.05, upper=Inf)) Then the probability to achieve a statically significant result in the planned study is 35. If the previous estimated effect was instead 1 then we get 71%. Hence, we get the same results as in the calculates above. Similarly, if the previous study was gigantic, the prior uncertainty is minimal and the probability of success will be equal to the power of the study. Previous setting have had a rather informative prior reflected belief with high certainty as reflected by a small value of the hyperparameter τ=0.40. We can allow for more uncertainty by using a vague prior with large value of τ, say 10.

N<- 63

SD <- 2

SE <- sqrt(2/N)*SD;

prior0 <- function(delta)dnorm(delta, 0.5, 10)

gb3<-round(100*gbayes2(sd = SE, prior = prior0, delta.w=0, alpha=0.05, upper=Inf))Then we get 49% which is higher than 35% because we now get more of the distribution in the right tail that favor a rejection of H0.

Simulating future studies based on prior predictive distribution

The calculations above combines Bayesian and frequentist philosophies. Since no data is being used (the previous study is just a metaphor for prior belief, it doesn´t matter how we got the information) and no posterior distribution is calculated. An alternative way is to make predictions from the prior distribution and evaluate the operating characteristics of these. This is called the prior predictive distribution.

f(Y)=∫θ,σf(Y|θ,σ2)⋅P(θ,σ2)dθσ

Lets say

Y∼N(θ0,τ20) θ0∼N([0,0.5],1) τ0∼half−t(3,0.5,2.5)

The prior mean value of θ0 is hence 0 and 0.5 for group A and B, respectively. We also evaluate for the prior θ0∼N([0,1.0],1) that is a mean difference of 1.0. The prior for σ is the default prior in the BRMS package.

By combining these prior distributions we can simulate data that is predictions of observations in future studies.

gc()

library(brms)

library(tidybayes)

library(tidymodels)

# Create dummy data for use when making the predictions from the prior

Empty <- tibble(Y = c(0, 0) , X = factor(c(0, 1), labels = c("A", "B")))

# Two scenarios: prior mu = 0.5 and 0.75.

prior_1 = c( prior(normal(0, 1), class = "b", coef = "XA"),

prior(normal(0.5, 1), class = "b", coef = "XB") )

prior_2 = c( prior(normal(0, 1), class = "b", coef = "XA"),

prior(normal(1, 1), class = "b", coef = "XB") )

fnc <- function(sz, P_, MU)

{

# Specify priors

prior_ = P_

# Set up the model to simulate from

BPr <- brms::brm(data = Empty,

family = gaussian,

Y ~ 0 + X,

prior = prior_,

sample_prior = TRUE ,

iter = 4000, warmup = 1000, chains = 4, cores = 4,

seed = 12)

# Make predictions of outcomes in future study based on the prior distribution

draws_prior <- Empty %>%

tidybayes::add_fitted_draws(BPr, n = 10000) %>%

mutate( Y = .value) %>%

dplyr::select(Y, X, .draw, .row)

df <- data.frame(draws_prior)

# Make repeated (1000 times) samples (i.e. "future studies") of given size.

df <- data.frame(draws_prior)

dfA <- subset(df, X=="A")

dfB <- subset(df, X=="B")

smplA <- infer::rep_sample_n( dfA, size=sz, replace = T, reps = 1000, prob = NULL)

smplB <- infer::rep_sample_n( dfB, size=sz, replace = T, reps = 1000, prob = NULL)

smpl0 <- rbind(smplA, smplB)

smpl <- smpl0 %>%

group_by(replicate, X) %>%

summarise(Average=mean(Y), SD=sd(Y), n=n()) %>%

group_by(replicate) %>%

mutate(Previous = lag(Average),

Mean_diff = Average - Previous,

LCL = Mean_diff - 1.96*sqrt(2/sz)*SD,

Reject=if_else(LCL<0, 0, 1)) %>%

filter(X=="B") %>%

mutate(Study.size = paste("N/group: ", sz, "Prior effect ", MU))

LST <- c(draws_prior, smpl)

return(LST)

}

# Percent of times lower 95% confidence interval is > 0

PoS1 <- fnc(sz=63, P_ = prior_1, MU=0.5)

gc()

PoS2 <- fnc(sz=63, P_ = prior_2, MU=1.0)

PoS1A <- tibble(Y=PoS1$Y, X=PoS1$X)

PoS1B <- tibble(Mean_diff=PoS1$Mean_diff, Reject=PoS1$Reject, Study.size=PoS1$Study.size)

PoS2A <- tibble(Y=PoS2$Y, X=PoS2$X)

PoS2B <- tibble(Mean_diff=PoS2$Mean_diff, Reject=PoS2$Reject, Study.size=PoS2$Study.size)

PoS11 <- round(100*(sum(PoS1B$Reject)/1000))

PoS21 <- round(100*(sum(PoS2B$Reject)/1000))

PoS<- rbind(PoS1B, PoS2B)

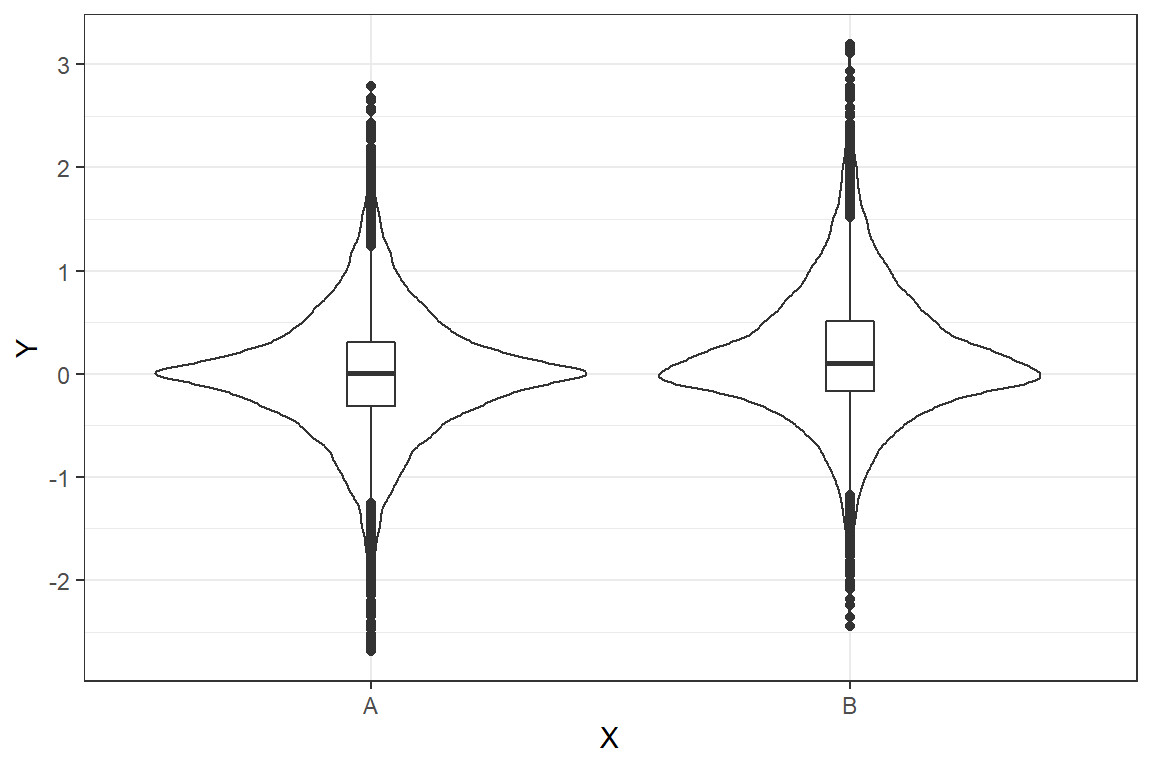

# Plot prior predictive distribution

fig2 <- ggplot(PoS1A, aes(x=X, y=Y)) +

theme_bw() +

geom_violin() +

geom_boxplot(width=0.1)

# Plot the distribution of the mean differences

fig3 <- ggplot(PoS, aes(x= Mean_diff, color=Study.size)) +

geom_density(aes(linetype=Study.size, color=Study.size), size=2) +

theme_bw() +

theme(legend.position="bottom") +

geom_vline(aes(xintercept=0), color="gray", linetype="dashed", size=1) The graph shows the prior predictions for θ0∼N([0,0.5],1). It is clear that for the current choice of priors data is far from normal - looks more like a double exponential distribution.

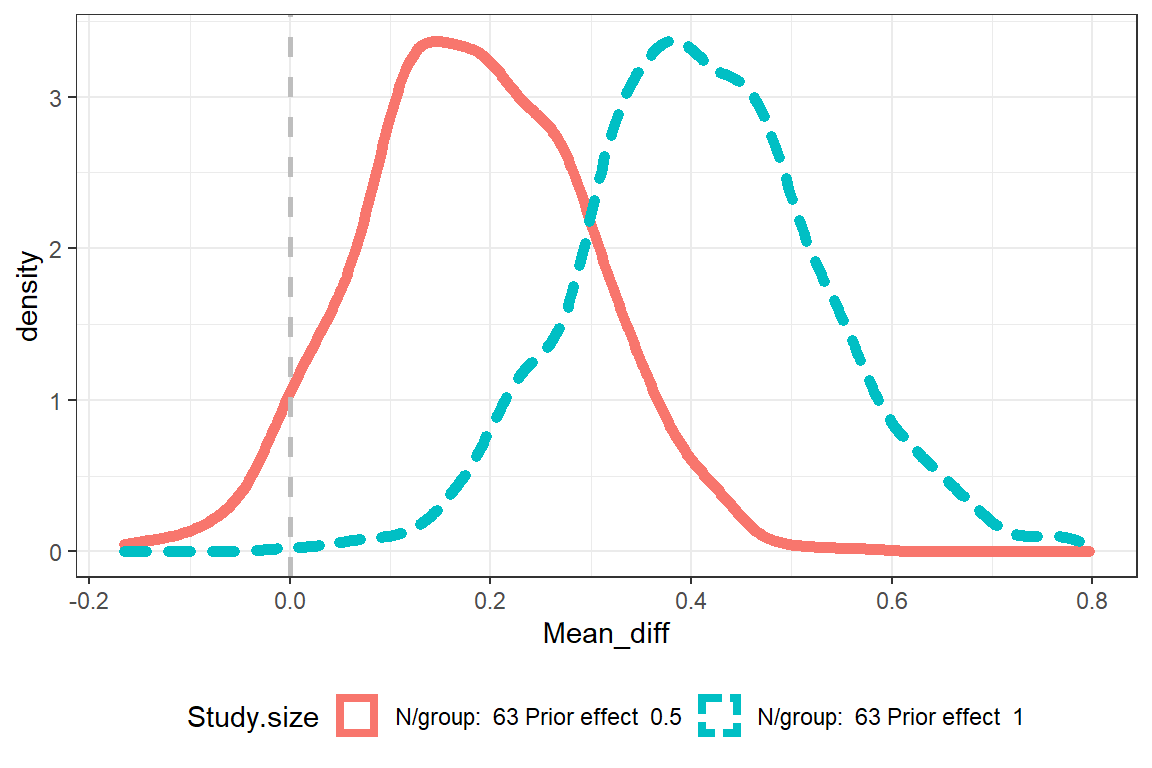

We see that for the prior θ0∼N([0,0.5],1) and a study size of 63 groups, Assurance (percent of times lower 95% CI is > 0) becomes 37%. For θ0∼N([0,1.0],1) it becomes 94%.

The plot shows the densities for the mean difference (¯x1−¯x2).

The Assurance does not become the same as in the previous calculations. There may be different reasons for this, e.g. how the priors was specified.

Concluding remarks

The greatness of the Bayesian approach is much more than being transparent about and systematic use prior knowledge. A major advantage of the Bayesian approach (as compared to the frequentist) is that it gives us a posterior distribution that provides relevant answers to our scientific questions. The frequentist point estimate and confidence interval is less informative for us (not to mention the p-value).

Some may find the choice of priors troublesome. But this problem is minor as compared to the benefits. You can chose whatever prior you like and does not necessarily only need to reflect the outcomes of previous studies. Other reasons for choice of prior is to calibrate the degree of regularization, e.g. by a horseshoe prior. A general advice is to decide on prior before analysing the data in order to ensure a high scientific integrity.

Simulating data based on prior distributions is a good way to assess the appropriateness of the prior by assessing if it will give rise to realistic data. A normal prior can provide L2-regularization (Ridge regression), see here. The variance σ2τ is the inverse of the degree of regularization. Our specification στ=1 is likely to impose too much regularization to be used in practice, but is merely used for illustration. Our use of the traditional definition of a positive study - a p-value<0.05 with a threshold of 0 was also used for illustration.